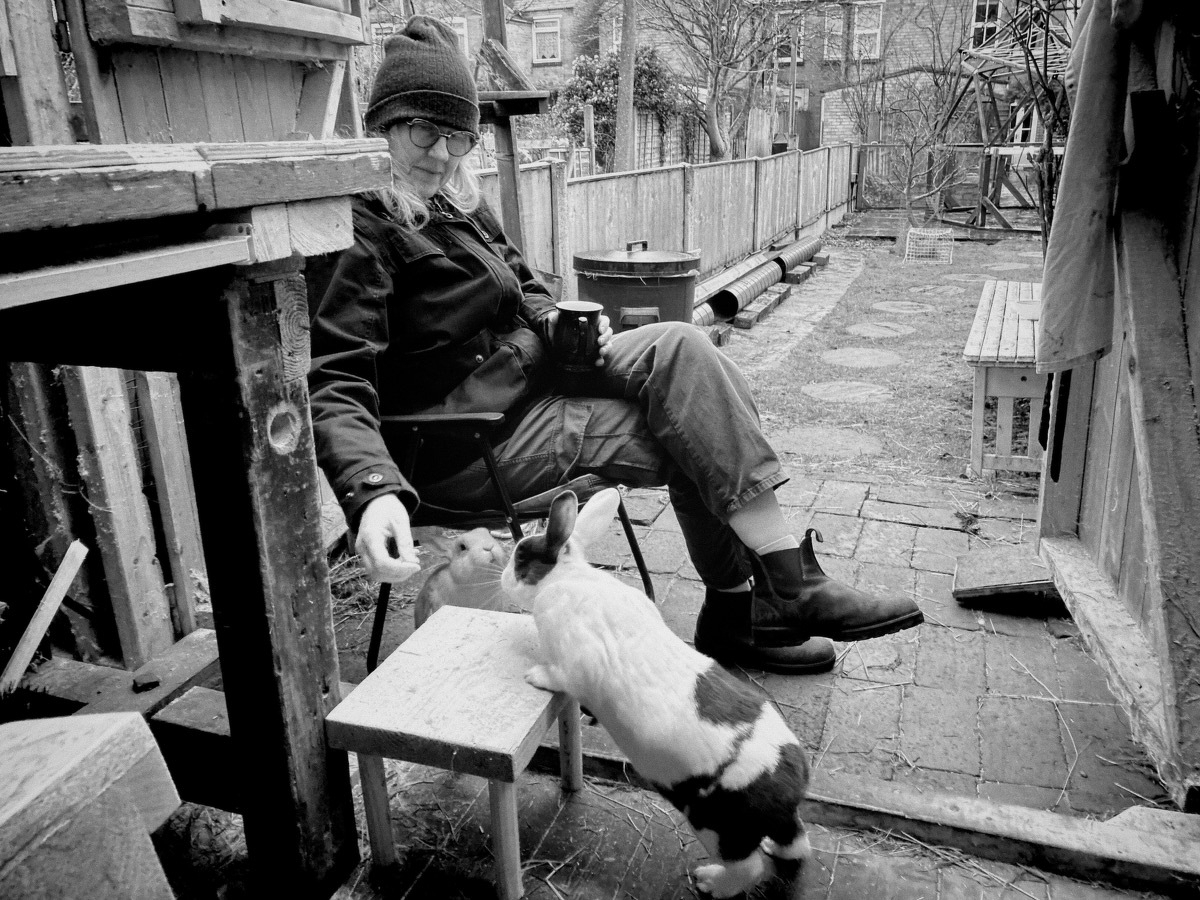

Shitty weather today but it’s nice in the shed.

Status:

Bit of a rough night with sweats and weird dreams, and then slept through most of the day. Feeling kinda antsy but trying to ride through it rather than act on it.

Andy came over to borrow my pressure washer and I was looking forward to inducting him (aged 38) into middle-age through the pursuit of cleaning paving stones with jets of water. It’s a rite of passage, like feeding a teen their first pint of bitter, but sadly the pressure washer decided not to switch on. He took it anyway because sometimes it does decide to switch on.

Then we had a nice chat about art and stuff, specifically the new film he wants to make which sounds exciting. Got me talking about when me and my mates would shoot photos with expired film around 2006, taking advantage of the moment when a lot of pro photographers were switching to digital and clearing out their stocks on eBay. That moment has long passed and film is dead expensive again. You don’t know you’re living in a golden age until it’s over.

This got me thinking about the art scenes and movements that occur in the backwash of industrial and economic change, which is probably most of them, and then I realised the conversation was getting far too interesting and I was getting a headache, so we called it a day.

Overnight listening:

I only managed a bit of In Our Time last night before having to switch to some music. I think I’ve reached the point where Melvyn Bragg is a bit of a prick (I’m working backwards and he mellows in later years), plus it’s the height of 2020 lockdowns so a lot of the academics are phoning in from home with terrible acoustics that stab my brain.

One of the milder tragedies of the early pandemic was broadcasters recording their end of a call with all the compression and aural artefacts. They should have gotten the contributor to make their own recording and then splice it all together in the edit. Even if they don’t have a decent mic it would be a marked improvement. Or just post them a decent mic.

So I’ve had a good run but it’s time to find something new to fall asleep to.

Reading:

Watching:

Telly: